Shooting a Dog

Fiction's Prophecy #14

“Take him, Mr. Finch.” Mr. Tate handed the rifle to Atticus; Jem and I nearly fainted.

--Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)

Atticus Finch did not own a gun. Yet one day he raised a rifle to his shoulder and shot a dog dead.

During a Depression summer in 1932, Finch is the unflinching conscience of Maycomb County, defending a Black man accused of raping a white woman. His client is innocent, and when an all-white jury returns a guilty verdict, Jem is devastated. Atticus explains his legal defeat with a lesson—a rejection of the idea that courage is a matter of dominance or force; rather, that it is defined by resolve even in the face of certain loss. “‘I wanted you to see what real courage is, instead of getting the idea that courage is a man with a gun in his hand. It’s when you know you’re licked before you begin, but you begin anyway and see it through no matter what.’” This is the moral grammar of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird.

Early in the novel, Atticus gives his children Jem and Scout a rule about guns that matters more than marksmanship: some lives (like a mockingbird) may never be taken, not because they are powerful, but because they do no harm at all. Later, when the menacing approach of a rabid dog drives the neighborhood folks indoors, the county sheriff arrives to deal with the danger. To Jem and Scout’s astonishment, he hands his rifle to Atticus, saying: “Take him, Mr. Finch.” Atticus accepts the weapon with visible reluctance; then fires off two clean shots. This is not an act of bravado, nor a display of power. There is no victory, only the terrible precision of necessity. The two shots are an act of care, not dominance. The dog is not an enemy; it is a danger. The task is not punishment, but prevention. Delay would be cruel; panic would be worse.

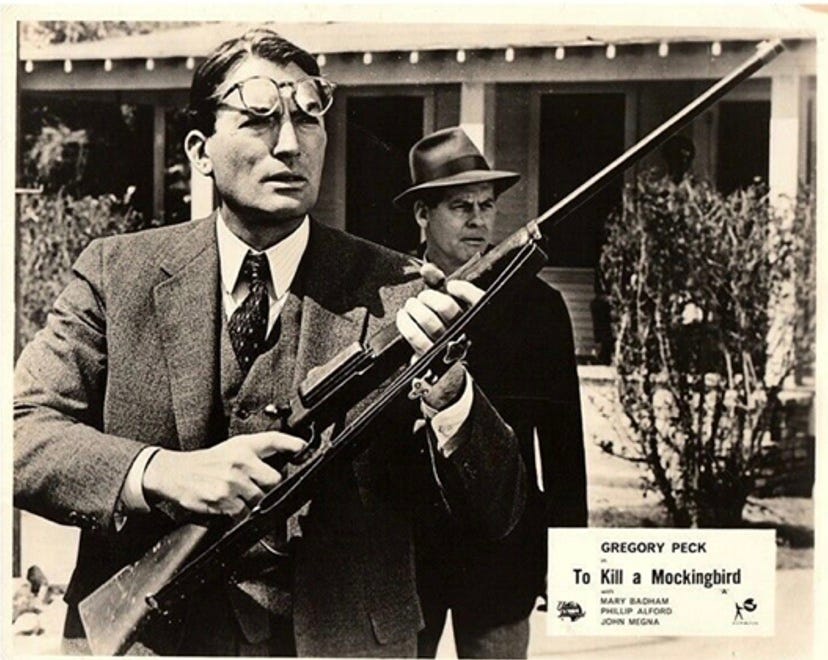

Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning performance in the 1962 film adaptation is uniquely authentic. His politics and character aligned closely with Finch’s: he was an advocate for racial justice and, in later years, openly critical of the increasingly expansive interpretation of the Second Amendment. Across his career, Peck gravitated toward—and was sought out for—roles that placed conscience above command: lawyers, journalists, reluctant leaders who stood upright against institutional wrong. He described Mockingbird as his favorite film, noting that it offered him a role he recognized immediately as necessary. As Atticus, Peck embodies a moral authority established not by refusing all force, but by refusing its misuse. Near the end of his life, reflecting on gun violence in the wake of the Columbine school massacre, Peck framed the issue not as ideology but responsibility:

“Is it the culture or the guns that led to the massacre at Columbine High School? And it is of course both. What is wrong with keeping guns out of the hands of the wrong people?”

What, indeed, is wrong with that? Lee’s novel does not argue about guns in the abstract. It situates one gun, in one moment, in the hands of one man whose character we have already come to trust. The man with the gun ends the suffering of one animal and protects a whole town. Detached from that character, the gun tells us nothing. Its meaning flows entirely from the conscience that guides the hand.

* * * * * * * * * *

The current Secretary of Homeland Security also shot a dog. In the summer of 2024, during the release of her political memoir, Kristi Noem publicly told of executing her fourteen-month-old wirehaired pointer, Cricket, in a gravel pit. He had proved disappointing at the hunt. Noem offered the story not with remorse but with pride, presenting the killing as proof of her toughness and resolve. The media exposure briefly appeared to threaten her political future. Instead, she is now elevated to a position overseeing a vast and heavily militarized federal enforcement apparatus—one marked by aggressive posture, minimal transparency, and expansive discretion. The recruits are ill-trained, and are promised forms of immunity that function as permission to act first and account for those actions later, or not at all.

Yesterday, on a freezing morning on a Minneapolis street far from the southern border, Alex Pretti was murdered by members of the federal Border Patrol under Noem’s authority. Pretti was protesting the earlier shooting death of Renee Good and the broader escalations of force, as masked agents flooded his city. He was present as a peaceful advocate and citizen witness; he was also legally carrying a handgun. While reaching out to help a woman who had been forcefully knocked to the ground, he too was tackled, his gun discovered and removed, and seconds later—prone on the pavement—he was shot in the back, point blank. Within minutes, and then for hours, a MAGA chorus insisted that the mere presence of a firearm made his death inevitable, perhaps even justified.

The hypocrisy could not be sharper. Some of the fiercest defenders of the Second Amendment—those who lionize open carry as an emblem of liberty—have now maligned a dead man simply for being armed. One of the loudest voices in this register belongs to Noem herself, who declared that Pretti “showed up to impede a law enforcement operation with a gun and ammunition, not a sign,” as if the presence of a firearm, rather than the decision to pull a trigger, were the decisive moral fact.

What defined Alex Pretti’s life, by all accounts, was a celebration of life, marked by a devotion to caring for others. A life like a mockingbird’s song. Atticus Finch knew the difference between a rabid dog and a mockingbird; the regime that governs us now is so impoverished that within it, the idea of the mockingbird no longer exists.

Well said, Jill. Principles are the crucial difference between Finch and Trump, Noem and their killers on ICE.

Jill, profoundly truthfully meaningfully said.